|

Burnside's North Carolina Expedition [February-June 1862]

"The enterprise of running the blockade and importing army supplies

from abroad has proven a complete success." Governor Zebulon Baird Vance, November 1863

Introduction

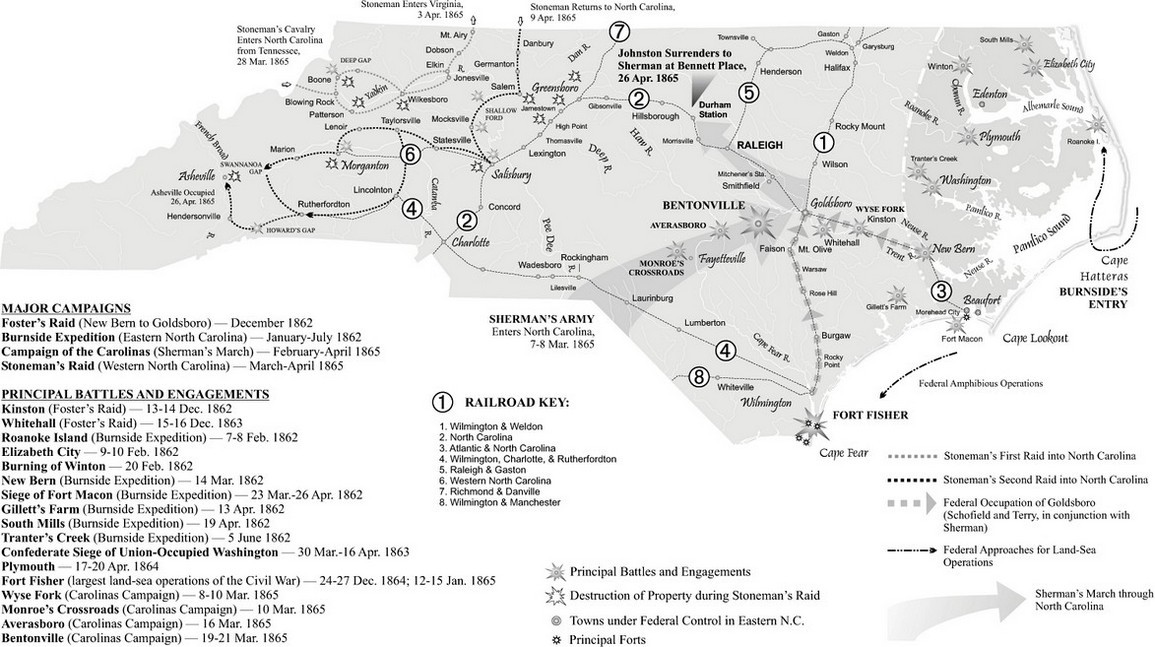

Burnside's North Carolina Expedition, commonly referred to as the Burnside Expedition, was an objective in Union

General Winfield Scott's Anaconda Plan and consisted of a series of battles along the North Carolina coast

during the American Civil War (1861-1865). In January 1862, an amphibious expedition under the command of Union Brig. Gen.

Ambrose E. Burnside was dispatched to the North Carolina coast to deprive the Confederacy of its

vital blockade-running ports. Hatteras Inlet, during the Blockade of the Carolina Coast, had been seized by Maj. Gen. Ben Butler in 1861. Next, Burnside was sent to take Roanoke Island, capture

the town of New Bern, move against Fort Macon, and proceed against the railroad at Kinston and Goldsboro. Despite the handicap of adverse weather, the first three

objectives of the expedition were successively achieved. The last objective, however, would have to wait.

| Burnside and North Carolina Expedition Map |

|

| Map of Burnside's North Carolina Expedition |

| Fort Huger on Roanoke Island, NC |

|

| (Formidable Civil War Fort) |

The principal objectives of Burnside's massive expedition were best

summarized in the detailed instructions finally issued to him by Maj. Gen. George McClellan on January 7, 1862. Moreover,

these instructions would prove more than a little prophetic of the future course of events in North Carolina during the balance

of the Civil War:

"In accordance with verbal instructions heretofore given you, you will, after

uniting with Flag-officer Goldsborough at Fort Monroe, proceed under his convoy to Hatteras inlet, where you will, in connection

with him, take the most prompt measures for crossing the fleet over the Bulkhead into the waters of the sound. Under the accompanying

general order constituting the Department of North Carolina, you will assume command of the garrison at Hatteras inlet, and

make such dispositions in regard to that place as your ulterior operations may render necessary, always being careful to provide

for the safety of that very important station in any contingency.

Your first point of attack will be Roanoke Island and its dependencies. It

is presumed that the navy can reduce the batteries on the marshes and cover the landing of your troops on the main island,

by which, in connection with a rapid movement of the gunboats to the northern extremity as soon as the marsh-battery is reduced,

it may be hoped to capture the entire garrison of the place. Having occupied the island and its dependencies, you will at

once proceed to the erection of the batteries and defences necessary to hold the position with a small force. Should the flag-officer

require any assistance in seizing or holding the debouches of the canal from Norfolk, you will please afford it to him.

The commodore and yourself having completed your arrangements in regard to

Roanoke Island and the waters north of it, you will please at once make a descent on New Berne, having gained possession of

which and the railroad passing through it, you will at once throw a sufficient force upon Beaufort and take the steps necessary

to reduce Fort Macon and open that port. When you seize New Berne you will endeavor to seize the railroad as far west as Goldsborough,

should circumstances favor such a movement. The temper of the people, the rebel force at hand, etc., will go far towards determining

the question as to how far west the railroad can be safely occupied and held. Should circumstances render it advisable to

seize and hold Raleigh, the main north and south line of railroad passing through Goldsborough should be so effectually destroyed

for considerable distances north and south of that point as to render it impossible for the rebels to use it to your disadvantage.

A great point would be gained, in any event, by the effectual destruction of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad. I would advise

great caution in moving so far into the interior as upon Raleigh. Having accomplished the objects mentioned, the next point

of interest would probably be Wilmington, the reduction of which may require that additional means shall be afforded you."

| Civil War Burnside Expedition Map |

|

| General Burnside's North Carolina Civil War Expedition |

| Roanoke Island and the Burnside Expedition |

|

| Official Map of Burnside's Expedition with emphasis on Roanoke Island |

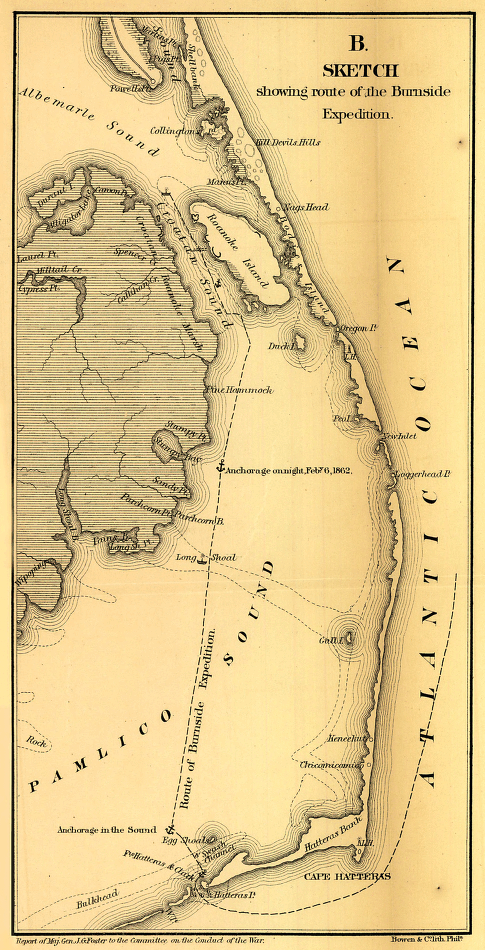

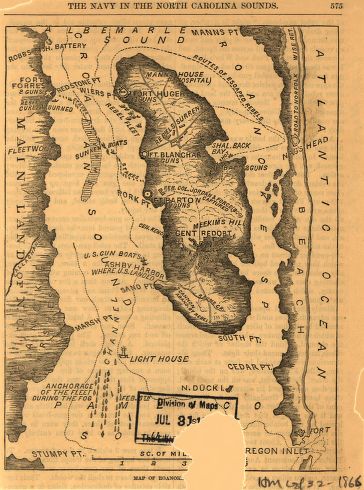

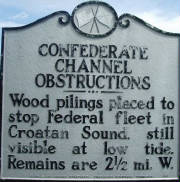

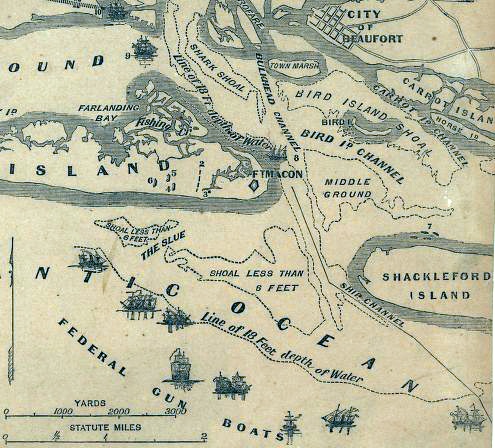

(Above) Map, February 8, 1862, with forts and batteries located on and adjacent strategic Roanoke Island,

NC. The island was also defended by a variety of channel obstructions, such as wood pilings which were designed to strike

the hull of a ship. The Confederate “mosquito

fleet” of small, shallow draft boats would attempt to lure Federal ships into the dangerous unmarked and obstructed

channel. (Right) Map of Burnside's initial route and advance to Roanoke

Island, which was the first of a series of battles in the Burnside Expedition. Courtesy Clark's North

Carolina Regiments.

Background

In August 1861, Maj.

Gen. Benjamin F. Butler and Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham captured Forts Hatteras and Clark guarding and entry point into

Pamlico Sound. It took several months before the Union high command would capitalize on this success. Butler and Stringham

were able to persuade the Secretary of Navy Gideon Welles to maintain a force at Hatteras Inlet to keep the possibility of

further operations open. The Lincoln Administration did not agree with invading North Carolina from the sea, but General-in-Chief

George B. McClellan was in favor of such an operation. McClellan was able to persuade President Lincoln to authorize the operation

and choose Brig. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside to lead the expedition. (In recognition of his successes at the battles of Roanoke

Island and New Bern, the first significant Union victories in the Eastern Theater, Burnside would be promoted to major general

of volunteers on March 18, 1862.)

| North Carolina Civil War Map |

|

| North Carolina Map of Civil War Battlefields |

During late January 1862, a Federal land-sea expedition

assembled at Hatteras Inlet to take Roanoke Island and capture control of the North Carolina sound region and its Outer Banks. The force was under the joint command of Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and navy Flag-Officer Louis Goldsborough. After

several delays due to bad weather, the Union fleet, consisting of dozens of troop transports and more than 20 war vessels,

arrived at the southern end of Roanoke Island. On Croatan Sound the South’s five-vessel

“Mosquito Fleet” harried the Union ships but was badly battered and quickly driven north out of range.

(Right) Map of the

principal battles fought in North Carolina.

Expedition

The Burnside Expedition, which was

contested during four months, consisted of the Battle of Roanoke Island (aka Fort Huger), Battle of Elizabeth City, Battle of New Bern (aka New Berne), Battle of Fort Macon, Battle of South Mills (aka Camden), and Battle of Tranter's Creek.

The Battle of Roanoke Island, February 7-8, 1862, was the initial battle of the Burnside Expedition. On Feb. 7, a hundred vessel Union flotilla

steamed down Croatan Sound to land an amphibious force on Roanoke Island after destroying a small Confederate fleet in Albemarle

and Pamlico sounds. Brig. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside led 15,000 U.S. Army troops while Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough commanded

the naval contingent. By capturing the island, the Federals would have a base from which to attack Confederates in North Carolina

from the sea. About 3,000 Confederate soldiers under Col. Henry M. Shaw opposed the landing, and Flag Officer William

F. Lynch’s three-gun battery and seven gunboats supported them. Three forts stood on the northwestern part of the twelve-mile-long

island, but were not positioned so they could help. Lynch led his gunboats out against the Federal fleet, but Goldsborough

defeated them and landed the Union troops at Ashby’s Harbor. By midnight, the Federals occupied the beach, and at 8:00

a.m. the next morning, they set off in pursuit of the Confederates, who were retreating north. About halfway up the island,

Burnside’s men encountered the battery and a force of 1,500 but soon outflanked them. The Confederates retreated once

again, then surrendered near the northern tip of Roanoke Island.

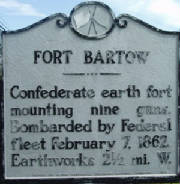

| Fort Bartow, North Carolina Coast |

|

| (Historical Marker) |

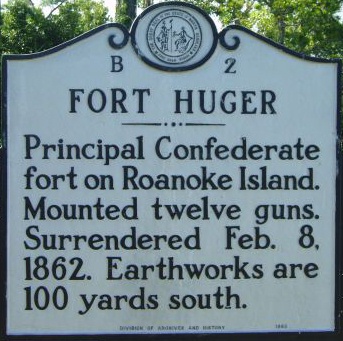

Fort

Bartow’s guns opened the Battle of Roanoke Island on

Feb. 7, and while the fort subsequently was bombarded by the Federal fleet for seven hours, it would continue to return

fire but with little effect.

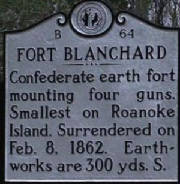

On Feb, 7, Federal ships

began a bombardment of the three Confederate earthen forts (Fort Bartow,

Fort Blanchard, and Fort

Huger) on the west side of Roanoke Island. Fort Huger was the

northernmost and largest of the forts with twelve guns mounted in its sand parapets. The forts were designed to protect the

mainland from Federal invasion and to complement obstructions placed in the channel. Forts Huger and Blanchard were not actively

engaged in the Battle of Roanoke Island and were ineffective in the battle because the Union fleet maintained a safe distance

relative to the range of the cannons placed at those forts. Bartow was the only island fort actively engaged in the fight.

| Confederate Inlet Obstructions |

|

| (Historical Marker) |

The Confederate fleet, under the command of Captain W. F. Lynch, waited to engage the Federals

behind a line of obstructions placed in Croatan Sound to retard the Federal advance. The line of obstructions in the

channel consisted of 16 sunken ships and pilings, which were meant to damage the undersides of ships passing through

the waters However, the Confederates, after a sharp engagement which was ended only by darkness, were forced to retire due

to lack of ammunition.

Southern strongholds

in the region included Fort Bartow, which was the southernmost Confederate defense.

It was one of three Confederate earthen forts on the west side of Roanoke Island (the others were Fort Huger and Fort Blanchard)

and it fort mounted nine guns. Of the three forts, Bartow was the only one actively engaged in the Battle of Roanoke Island.

Constructed in the fall

of 1861 of reinforced sand, Fort Blanchard

was the smallest of the three and mounted four guns. The fort saw no action during the Battle of Roanoke Island as its guns

were out of range of the main Federal operations. Fort Blanchard was surrendered on February 8, 1862. Mounted with twelve guns, Fort Huger was the principal Confederate fort on Roanoke

Island. It too was surrendered on Feb. 8.

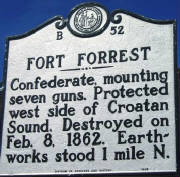

| Fort Forrest, North Carolina |

|

| (Historical Marker) |

Fort

Forrest was a small mainland Confederate fortification on the western side of Croatan Sound and it consisted

of two shore bound barges equipped with seven 32 pound cannon. The position was directly opposite Fort

Blanchard on Roanoke Island and its construction

amounted to an attempt to block passage through the channel by Union gun boats. Fort

Forrest would be destroyed by Federal forces during the second day

of fighting.

| Fort Blanchard, NC |

|

| (Historical Marker) |

On Feb. 8, the Federal fleet

again bombarded various positions on Roanoke Island including Fort Blanchard and Fort Forrest in support of General Burnside’s

land offensive. After the Union victory on the afternoon, a detachment of Federal ships under the command of Commodore S.

C. Rowan was sent into Albemarle Sound in pursuit of the Confederate fleet. As a consequence,

Union forces were in control of most of the inland waters of northeastern North

Carolina.

Burnside next turned his attention and efforts on New Bern (spelled New

Berne at the time). Confederate General Lawrence O. Branch, commanding an inadequate number of troops in that area, decided

to defend the city in fortifications located approximately six miles south and adjacent the Neuse River. Burnside, however, landed his men twelve miles downriver on March 13 and began marching toward

New Bern. Determined to smash the Union invaders, Branch had redeployed his Rebel force closer to the city, and his men now

braced for the attack, which began the next morning.

Although the Confederates withstood the advancing Union troops for several

hours, eventually the Rebel center collapsed, and Branch’s soldiers retreated. Some Confederates, after they crossed

the Trent River into New Bern, and as Federal gunboats shelled them, burned the bridge behind them.

Realizing his position was untenable, Branch withdrew his men by rail

to Kinston. Burnside’s powerful force occupied New Bern the next day, and remained in Federal hands until the end of the war. Confederate General

George E. Pickett attempted to recapture it in 1864 but failed. Burnside would next move on and then capture both Beaufort

and the Southern stronghold Fort Macon. For his laudable successes, Burnside would

be promoted on March 18.

| North Carolina Coastal Defenses |

|

| North Carolina Outer Banks and its Defenses during the Civil War |

| Vital Fort Macon (Center) and City of Beaufort |

|

| Vital Fort Macon (Center) and City of Beaufort |

(Map) Entrance to Beaufort harbor, N.C., showing the position of Fort Macon

and vicinity.

(References listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended

Reading: Gray Raiders of the Sea: How Eight Confederate Warships Destroyed the Union's

High Seas Commerce. Reader’s Review:

This subject is one of the most fascinating in the history of sea power, and the general public has needed a reliable single-volume

reference on it for some time. The story of the eight Confederate privateers and their attempt to bring Union trade to a halt

seems to break every rule of common sense. How could so few be so successful against so many? The United

States, after Great Britain,

had the most valuable and extensive import/export trade in the world by the middle of the 19th century. The British themselves

were worried since they were in danger of being surpassed in the same manner that their own sea traders had surpassed the

Dutch early in the 18th century. Continued below…

From its founding

in 1861, the Confederate States of America realized it had a huge problem since it lacked a navy.

It also saw that it couldn't build one, especially after the fall of its biggest port, New

Orleans, in 1862. The vast majority of shipbuilders and men with maritime skills lived north of the

Mason-Dixon Line, in the United States, and mostly in New

England. This put an incredible burden on the Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen R. Mallory. When he saw

that most of the enemy navy was being used to blockade the thousands of miles of Confederate coasts, however, he saw an opportunity

for the use of privateers. Mallory sent Archibald Bulloch, a Georgian and the future maternal grandfather of Theodore Roosevelt,

to England to purchase British-made vessels

that the Confederacy could send out to prey on Union merchant ships. Bulloch's long experience with the sea enabled him to

buy good ships, including the vessels that became the most feared of the Confederate privateers - the Alabama,

the Florida, and the Shenandoah. Matthew Fontaine Maury

added the British-built Georgia, and the Confederacy itself launched the

Sumter, the Nashville, the Tallahassee,

and the Chickamauga - though these were generally not as effective

commerce raiders as the first four. This popular history details the history of the eight vessels in question, and gives detailed

biographical information on their captains, officers, and crews. The author relates the careers of Raphael Semmes, John Newland

Maffitt, Charles Manigault Morris, James Iredell Waddell, Charles W. Read, and others with great enthusiasm. "Gray Raiders"

is a great basic introduction to the privateers of the Confederacy. More than eighty black and white illustrations help the

reader to visualize their dramatic exploits, and an appendix lists all the captured vessels. I highly recommend it to everyone

interested in the Confederacy, and also to all naval and military history lovers.

Burnside's North Carolina Expedition [February-June 1862]

North Carolina Coast and the American Civil War

Recommended Reading: Ironclads and Columbiads: The Coast

(The Civil War in North Carolina) (456 pages). Description: Ironclads and Columbiads covers some of the most

important battles and campaigns in the state. In January 1862, Union forces began in earnest to occupy crucial points on the

North Carolina coast. Within six months, Union army and

naval forces effectively controlled coastal North Carolina from the Virginia

line south to present-day Morehead City.

Continued below...

Union setbacks in Virginia, however, led to the withdrawal of many federal soldiers from North Carolina,

leaving only enough Union troops to hold a few coastal strongholds—the vital ports and railroad junctions. The South

during the Civil War, moreover, hotly contested the North’s ability to maintain its grip on these key coastal strongholds.

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in North Carolina. Description: Numerous

battles and skirmishes were fought in North Carolina during

the Civil War, and the campaigns and battles themselves were crucial in the grand strategy of the conflict and involved some

of the most famous generals of the war. John Barrett presents the complete story of military engagements across the state,

including the classical pitched battle of Bentonville--involving Generals Joe Johnston and William Sherman--the siege of Fort Fisher, the amphibious

campaigns on the coast, and cavalry sweeps such as General George Stoneman's Raid.

Recommended Reading:

The Civil War in Coastal North Carolina (175 pages) (North Carolina Division

of Archives and History). Description: From the drama

of blockade-running to graphic descriptions of battles on the state's islands and sounds, this book portrays the explosive

events that took place in North Carolina's coastal region during the Civil War. Topics discussed include the strategic

importance of coastal North Carolina, Federal occupation

of coastal areas, blockade-running, and the impact of war on civilians along the Tar Heel coast.

Recommended Reading: Storm

over Carolina: The Confederate Navy's Struggle for Eastern North Carolina. Description: The struggle for control of the eastern

waters of North Carolina during the War Between the States

was a bitter, painful, and sometimes humiliating one for the Confederate navy. No better example exists of the classic adage,

"Too little, too late." Burdened by the lack of adequate warships, construction facilities, and even ammunition, the

South's naval arm fought bravely and even recklessly to stem the tide of the Federal invasion of North

Carolina from the raging Atlantic. Storm

Over Carolina is the account of the Southern navy's struggle in North

Carolina waters and it is a saga of crushing defeats interspersed with moments of brilliant and even

spectacular victories. It is also the story of dogged Southern determination and incredible perseverance in the face

of overwhelming odds. Continued below...

For most of

the Civil War, the navigable portions of the Roanoke, Tar, Neuse, Chowan, and Pasquotank rivers were

occupied by Federal forces. The Albemarle and Pamlico sounds, as well as most of the coastal towns and counties, were also

under Union control. With the building of the river ironclads, the Confederate navy at last could strike a telling blow against

the invaders, but they were slowly overtaken by events elsewhere. With the war grinding to a close, the last Confederate vessel

in North Carolina waters was destroyed. William T. Sherman

was approaching from the south, Wilmington was lost, and the

Confederacy reeled as if from a mortal blow. For the Confederate navy, and even more so for the besieged citizens of eastern

North Carolina, these were stormy days indeed. Storm Over Carolina describes their story, their struggle, their history.

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in the Carolinas (Hardcover). Description: Dan Morrill relates the experience of two quite different states bound together in

the defense of the Confederacy, using letters, diaries, memoirs, and reports. He shows

how the innovative operations of the Union army and navy along the coast and in the bays and rivers of the Carolinas

affected the general course of the war as well as the daily lives of all Carolinians. He demonstrates the "total war" for

North Carolina's vital coastal railroads and ports. In

the latter part of the war, he describes how Sherman's operation

cut out the heart of the last stronghold of the South. Continued below...

The author

offers fascinating sketches of major and minor personalities, including the new president and state governors, Generals Lee,

Beauregard, Pickett, Sherman, D.H. Hill, and Joseph E. Johnston. Rebels and abolitionists, pacifists and unionists, slaves

and freed men and women, all influential, all placed in their context with clear-eyed precision. If he were wielding a needle

instead of a pen, his tapestry would offer us a complete picture of a people at war. Midwest Book Review: The Civil War in the Carolinas by civil war expert and historian

Dan Morrill (History Department, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and Director of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historical

Society) is a dramatically presented and extensively researched survey and analysis of the impact the American Civil War had

upon the states of North Carolina and South Carolina, and the people who called these states their home. A meticulous, scholarly,

and thoroughly engaging examination of the details of history and the sweeping change that the war wrought for everyone, The

Civil War In The Carolinas is a welcome and informative addition to American Civil War Studies reference collections.

References: John G. Barrett, The

Civil War in North Carolina (1963); John Stephen Carbone, The Civil War in Coastal North Carolina (2001); Lorenzo Traver, Burnside Expedition in North

Carolina: Battles of Roanoke Island and Elizabeth

City (1880); Richard Allen Sauers, The Burnside Expedition in North Carolina (1996); North Carolina Office of Archives and History;

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Library of Congress; National Archives.

|